Understanding Differentiation

Differentiated Instruction has a mixed reputation. It’s seen as potentially transformative, allowing all students to learn and understand the lessons and materials in the classroom. It sounds like a great philosophy and ideal, almost like the dream of a perfect school. Yet the devil is in the details- how do we make this dream a reality? How can I start to differentiate in my class? Where do I start?

Many teachers assume that DI is impossible, because they assume it will require essentially individualized lesson plans for each kid in the classroom. When it’s often difficult to make sure kids with IEP’s get the accommodations they need, how would this work if every kid had their own plan? It’s enough to make anyone crazy. But let’s take a moment and look at another profession where people need to be treated as individuals, but without a group template or process, it simply wouldn’t work at all- Medicine.

My husband’s an OB-GYN. He knows how the whole process works, from conception to delivery and beyond, and generally what tends to go wrong in between. He needs to be a good diagnostician, which means being able to tell when a patient is progressing according to the general plan, and when their condition deviates from the norm and needs special attention. He has to recognize some problems before they occur, and prescribe treatments to prevent conditions, as well as treat problems when they come up. This is taking a basic treatment model for a condition- “pregnancy” and applying it to all different people, of different ages, races, with pre-existing conditions and more, and tweeking it just a little to make sure the outcome is the best it can be for two patients- Mother and Baby.

If we apply this same template to teachers, teachers have to know how a normal student progresses through the year. But then the teacher has to look for warning signs of a kid being in trouble before they actually get there, and do what’s needed to prevent problems before the occur. They also have to know how to help kids who are really struggling, and know what tips or alternatives to use to make sure that child gets what they need as well. That’s differentiating.

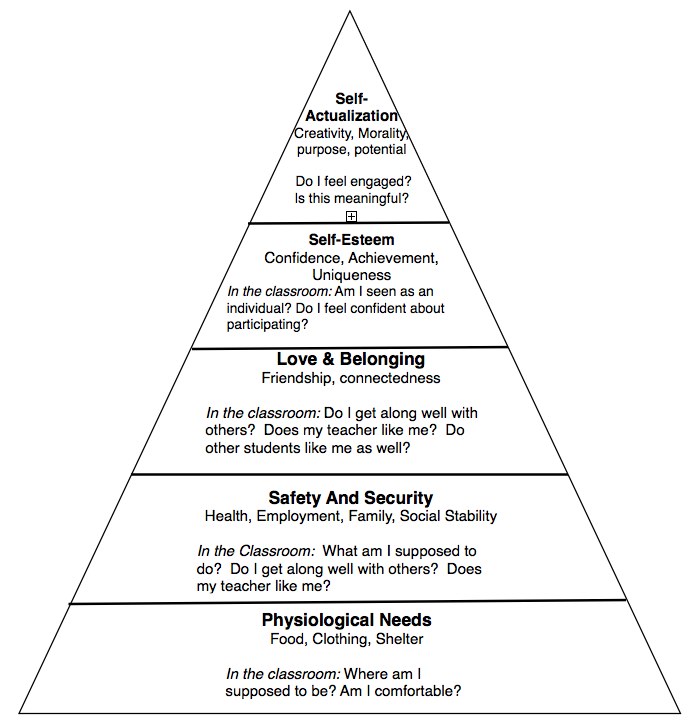

In our book, Jenifer and I discuss the hierarchy of needs in the classroom, based loosely on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. We made the following chart:

When students are in the classroom, they need to have their basic needs for “food clothing and shelter” met before they can really concentrate on the bigger things they need to concentrate on, like learning. This means one of the key, foundational elements any teacher can do is create a classroom environment where kids feel safe and welcomed.

When students are in the classroom, they need to have their basic needs for “food clothing and shelter” met before they can really concentrate on the bigger things they need to concentrate on, like learning. This means one of the key, foundational elements any teacher can do is create a classroom environment where kids feel safe and welcomed.

If you’ve ever wondered why we insist kids have a good breakfast every morning, it’s in part to make sure they have the energy to learn, but it’s also so they are not distracted by worrying about being hungry. Some teachers I know even keep a box of snacks in their classroom- packets of goldfish or other things- to help make sure any hungry child has something to eat. It makes the children feel more secure, and it makes the job o teaching just a little easier for the teacher as well. Some other teachers keep a few hoodies or big sweaters from a thrift shop in the classroom, in case a child is cold for the very same reasons- when a child has a basic comfort need unmet, the chances they will concentrate on the business of the classroom goes down.

This is why the first step to creating a great classroom, even before we start talking about other steps to differentiate instruction,it’s about creating a classroom where you and the kids feel comfortable. Maybe even like a “third period family” for the time they are with you.

The more the kids have a sense of what is expected, that you will be fair, and that they are expected to respect each other, the more willing they will be to take risks and make mistakes when learning. They’ll be more willing to go try a problem on a board or work in a group if they feel comfortable and that they won’t be humiliated or singled out for sharing their ideas.

By understanding a bit about Maslow’s hierarchy and how it effects a student’s motivation to learn and willingness to take risks, it will be easier to start thinking about ways to meet the individual needs of the students in your classroom. And just like a doctor, the changes will often be changes that apply to many kids, not just one, and the small tweeks to head off problems in advance will serve everyone in the classroom well.