Reflective Practice

I’ve been re-reading Scott McLeod and Chris Lehmann’s great book on What School Leaders Need to Know About Digital Technologies and Social Media. (You should really get a copy- it’s even on Kindle!) There is a great section on using blogging in conjunction with the classroom, and how it has helped instill a level of reflection for many students when used in conjunction with other projects. The interactive nature and the feedback it can offer- not just from peers or a teacher, but from the world at large, seems to inspire more thought and reflection in students than I’ve ever seen with any other traditional classroom practice.

When I went to my first education conference and there were long periods built in for reflection, I wasn’t sure exactly how to use this time. I had been so used to going from session to session, activity to activity, in school and in life, that having time set aside just to think and reflect and digest information seemed almost foreign. Yet we know reflection is a way to consolidate learning, and to examine, perhaps in detail, what’s going well and what’s not, which enables us to, in theory, come up with new approaches to confounding problems. But where do we teach this practice to students? Do we make time for it in the school day? Do we make time for it in the classroom? Is it appropriate to start teaching it, and if so, when? Is there a developmentally appropriate point to institute reflection in the classroom?

Most of the kids I know basically look at the test, paper, quiz, or project as the culmination of their learning. Teachers would call this an assessment of mastery, and parents might call it a pain, especially if it involves more than one trip to the craft store. What happens after the assessment or project is completed? For most kids, they get their grade, or a paper back, and unless it is meant as a draft, very little review and reflection of the work is done. The test is crammed into a folder or backpack, or if it’s a really good grade, displayed on the fridge, and that’s the end of it.

The only structured reflection time that went on in most of my schooling was either when I came home with a 90 on the test and my Dad asked where the other 10% was, and I felt dejected, or when I was sent to my room for some infraction and asked to “Think about what you did and we’ll talk later.” This latter form of reflection merely involved me sitting in my room, reading, playing with toys or otherwise enjoying the quiet from the fight, and perhaps a small amount of time devoted to trying to guess what I had done wrong in my parent’s eyes and guess what they wanted to hear so I could get out of trouble and move on as soon as possible. I suspect for many of you, this isn’t unfamiliar territory and the story hits pretty close to the mark.

However, after reading about the teachers using blogging in the classroom, I realized how perfect this is to instill reflection into school and learning. Just as I’m using this post to reflect on my experiences, kids could use a blog, whether classroom or personal, as a more open journaling experience, with a wider (and possibly more accepting) audience. They can trade ideas, and flesh out their thoughts as they commit them to writing rather than as fleeting clouds across their minds. It will give extra practice in writing and developing style and voice, in a way that so many other “5 paragraph essay” assignments just don’t. When feedback between a teacher and the students is an open exchange, the trust grows, and the dialog is no longer just one on one but communal.

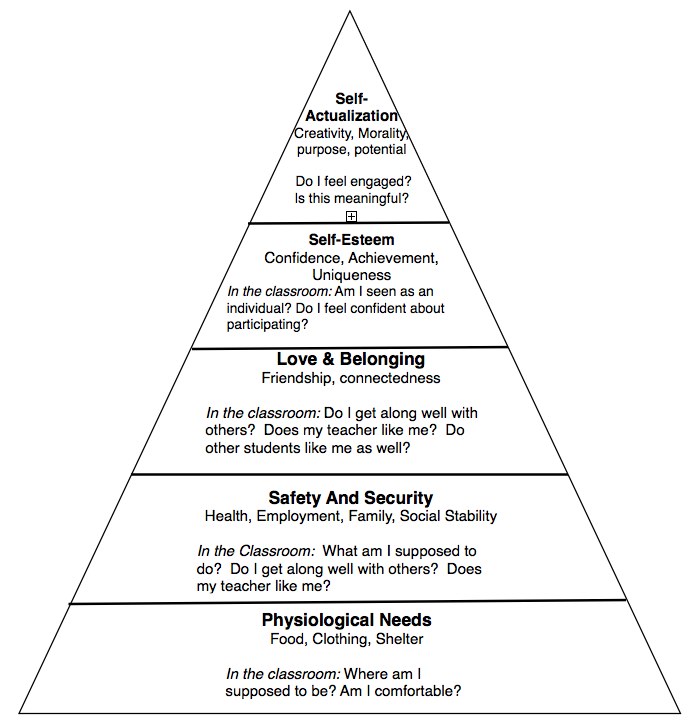

If we want students to truly improve over time, maybe spending time meaningfully not just “going over the test” but to start differentiating instruction and using assessments as diagnostic about what students have mastered and where they need more support would be more appropriate. Maybe asking students to do small reflections about projects and assignments, giving feedback about what they thought went well, what was harder, and even give them reinforcement for honesty such as “I didn’t manage my time well on this assignment” . This then allows an opportunity to give the time management kids additional support or scaffolding on the next assignment, to help them grow until they are ready to fly solo then just blindly expecting them to do “better.”

I think incorporating reflection in a more meaningful way into our classrooms is critical to build the 21st century skills of collaboration, creativity, critical thinking and communication we all say are important. The trick is doing it on a consistent basis, and in a way that seems more coach like and less as an additional opportunity to criticize and bash a kid who is already struggling. That’s why they never want to look at the paper with a sea of red- the assignment is over- it’s time to let the wound heal and try “better” next time. But they won’t get better unless we can give them the tools hthey need- and they see the point in udsing these tools- to get a different result the next time.

Otherwise, we’re all just living the embodiment of this quote:

“The Definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.”