Education Reform

I saw the Frontline documentary on Michelle Rhee last night, and it left me with as many questions as answers.

Public education is tricky because it’s non-uniform. School districts vary based on location, funding, resources, demographics- you name it. As much as we would like it to be standard and consistent, the reality is quite different. For example, our local middle school is a modern building, with smart boards in every classroom. Technology is used in almost every aspect of learning, from a digital grade book to online assessments, to students submitting multimedia projects via email and dropbox. The students come from a wide variety of homes, ranging from kids of professionals to those of migrant workers. A middle school I visited in North Carolina this fall had almost 100% minority population, where there were 4 smart boards in the whole school, and one cart of laptops that were held for the sole use of Title I students, and as a result, were rarely used at all. Teachers often did not assign homework, because many of their students were spending the evenings caring for parents and siblings, and legitimately could not be counted on doing work outside the classroom according to the teachers.

In the world of national standards, all the students in both schools are to be held to the same standard of learning, and the teachers to the same level of achievement for their students. This makes sense, in that once all these students hit the real world, they will all be competing for the same spots in college or the job market with students from more affluent and academically challenging environments. How do we make sure that the kids in this particular North Carolina school receive an education that will enable them to effectively compete with kids from our local school? How do we start to attack the problem?

Michelle Rhee, according to the Frontline documentary, found all sorts of problems in the DC schools. She set a goal of doing what was best for students, and keeping their interest at heart, which ended up involving getting rid of a lot of teachers and principals that were deemed to be under-performing, and closing schools with low enrollment. Closing schools and consolidating in order to avoid wasting money on building expenses and duplicate resources (including personnel) makes logical sense- especially when it provides additional funds for all the students in the District in the bargain. That’s simply good management, but it’s painful, since it meant jobs were eliminated and some kids would no longer be going to their neighborhood school.

The Gates Foundation released a report this week addressing what it has found to be potential better metrics for teacher evaluation. They also have released some metrics on personalized learning, which reflects much of what we discuss here on differentiating instruction:

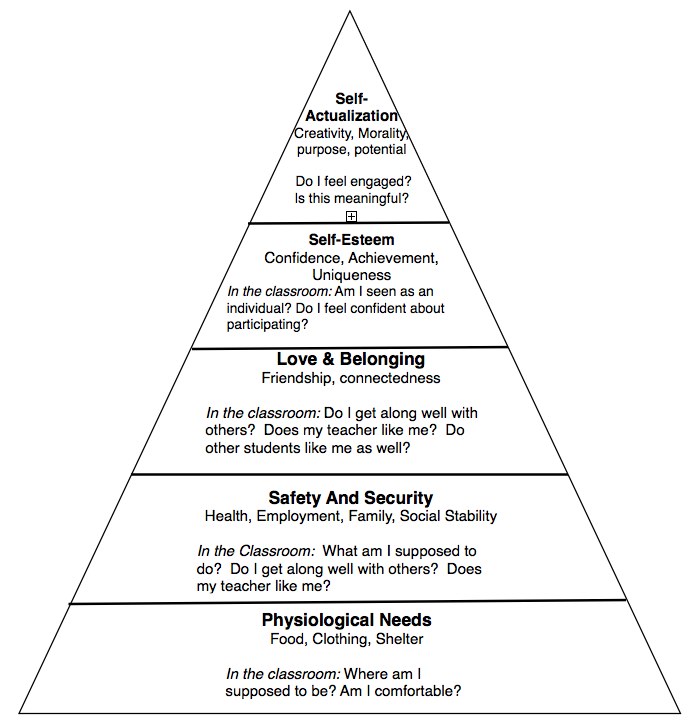

There is a small but growing effort to rethink fundamental aspects of our current system. The central idea is that the system should be designed not for uniformity, but instead to meet every student’s individual needs. At the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, we call this a shift to personalized learning. We are particularly interested in whole-school models that incorporate each of the following principles:

- Student Centered: designed to meet the diverse learning needs of each student every day

- High Expectations: committed to ensuring that every student will meet clearly defined, rigorous standards that will prepare them for success in college and career

- Self-Pacing & Mastery-Based Credit: enables students to move at their own optimal pace, and receive credit when they can demonstrate mastery of the material

- Blended Instruction: optimizes teacher- and technology-delivered instruction in group and individual work

- Student Ownership: empowers students with skills, information and tools they need to manage their own learning

- Financial Sustainability: sustainable on public per-pupil revenue within four years

- Scalable: designed to serve many more students if it demonstrates impact

It’s clear that effective teaching requires not only a thorough knowledge of the curriculum, but a sense of the students and connecting with them to make learning vibrant and exciting. That’s not always an easy task.

Even in the after school program where I volunteer, I know that I get better at running my class each time I do it, and that it requires reflection, asking the students about what went well and what didn’t, and considering what to tweek and try differently the next time. I know that the mix of students I get also changes what I can do and I need to be adaptive to student needs, not just wedded to my idea of a utopian curriculum. The overall critical points need to be taught, but the order and the method I choose might vary, depending on the day and the mood of the kids, as well as whether all the tech is working properly. The key, I’ve found, is to use my base knowledge and my general plan as a base or launch pad for the actual teaching that is done, which involves a bit of improv. From talking with academic full time teachers, they also say that the lesson plan is like any battle plan- it never fully survives contact with the enemy, as they say in the military- the enemy gets a say as well, or in this case, the students get a vote in how the lesson is going to go, and how much of the plan gets executed as written or needs to flex as needed.

This being said, metrics on judging teaching needs to be part “the plan” and another part “the execution” along with outcomes- how well did the kids actually absorb what you were trying to teach them? How effective are they at applying that knowledge to a new and novel situation?

Teachers don’t graduate from school with all these skills in place. They need on the job mentoring, and continuing education. They need a place where they can ask questions, share tips and tricks, and engage with colleagues in a safe environment, where they can admit what’s going well and where they may have challenges, without always feeling like their job is on the line if they admit any weakness. But at the same time, kids deserve to be taught by someone who knows what they’re doing, just like every patient deserves good medical care, even from a doctor who just finished their residency. We know these teachers and doctors will get better the more experience they have, but helping them learn to be better requires acknowledgement they aren’t perfect, just like no student or patient is perfect as well.

I admire Michelle Rhee for making some tough decisions and not running a popularity contest. I admire her for putting kids first, but part of that is also treating the adults in charge of the student’s learning with compassion and guidance as well as consequences for non-performance.

Teacher’s unions have often defended teachers who have been shown to be ineffective, based on longevity, tenure, or other reasons, and that’s clearly not always appropriate. Michelle Rhee’s monetary incentives to teachers and schools for achievement improvements may very well have lead to cheating, in order for the adults in the game to profit from those outcomes. Yet if the incentives were placed differently- instead of cash bonuses in every teacher pocket, could the incentives be more “team based” in terms of more resources for the students and schools for higher achievement? Could the incentives be placed in such a way everyone in the school benefitted instead of just the teachers or administrators, especially since it was based on student achievement and what the students themselves accomplished? I think you might still find teachers willing to tamper with results if it meant a laptop for every student in the school, but probably less frequently than if it meant an extra $8,000 in their paycheck.

We ask much more of teachers now than in the past. Some teachers have even lost their lives protecting their students, and if we’re going to ask for that level of commitment, we had better learn to respect them and compensate them for that difficult work. The perceived harshness of Michelle Rhee, even in the name of progress and reform, caused as many problems as she tried to solve. Perhaps working with appropriate carrots and sticks is really the best way to work towards education reform, rather than taking a slash and burn approach, no matter how much we may all need a real wake up call.

And for the rest of us out there, including myself, who assume we know everything about education because we went to school ourselves, we have to be patient and realize that solving the education issues in our Country may be much more personalized per school, per district, and per state than pushed down in a top down approach from the Department of Education.

Watch the Frontline special below:

Watch The Education of Michelle Rhee on PBS. See more from FRONTLINE.