Making Homework Matter- Differentiate The Homework

In our book, Jenifer and I knew we’d have to address homework. It’s one of the issues that constantly puts teachers, students and parents at odds. The real issue with homework is that kids often don’t see the point and it seems like busy work, rather than something that seems to have value. Can you blame kids? I can’t begin to tell you how many times my kids have said things like “She never checks the homework, so really, why should I do it?” It’s not that they don’t understand the value of practice, but they do look at it as the teacher assigns homework, but seems not to care or be invested in whether the work is actually done or not. Is it any wonder why they see no real reason to complete it and stop caring as well?

The New York Times wrote about the topic, in a great opinion piece entitled “The Trouble with Homework.” One great quote is the following:

In a 2008 survey, one-third of parents polled rated the quality of their children’s homework assignments as fair or poor, and 4 in 10 said they believed that some or a great deal of homework was busywork. A new study, coming in the Economics of Education Review, reports that homework in science, English and history has “little to no impact” on student test scores. (The authors did note a positive effect for math homework.) Enriching children’s classroom learning requires making homework not shorter or longer, but smarter.

In the first chapter of our book, Jenifer and I came up with many ways teachers can differentiate the homework, making it more personally relevant for each child in the classroom. In the best of circumstances, homework should be work that should be done individually, whether it’s practice, reflective work, or other work that frankly doesn’t require the audience and collaboration of the classroom itself. By using homework to prepare for class discussions the next day, to make sure that students have critical pieces of projects dine and ready for group work and the like, makes it more likely that the homework will get done, and that it has meaning.

Making homework meaningful also means making class time more meaningful. If you are together with thirty other students, shouldn’t this be a time to share ideas and collaborate? To learn from and with each other? If kids are spending class time doing things like sustained silent reading, this is in some ways wasting the purpose of spending time together in the class, unless the purpose of the exercise is learning to read in a library or public setting.

Assessments can also be part of homework, Instead of looking at assessments as tests taken during the day, how about trying to give kids open ended questions or novel problems where they have to take what they’ve been learning and apply it to solve a bigger problem? This gives kids more time to really display what they know, and show mastery (or lack thereof) on assignments in a way that a multiple choice test in class never will.

We also encourage teachers to try to make homework interactive. Sometimes this can be reading an article and commenting on it on a classroom blog or wiki. It could be assembling artifacts about a topic on their own wiki, or with a group. It could be participating in a discussion through Skype. Any of these assignments give kids an opportunity to express themselves as well as serving as a jumping off point for classroom discussions the next day.

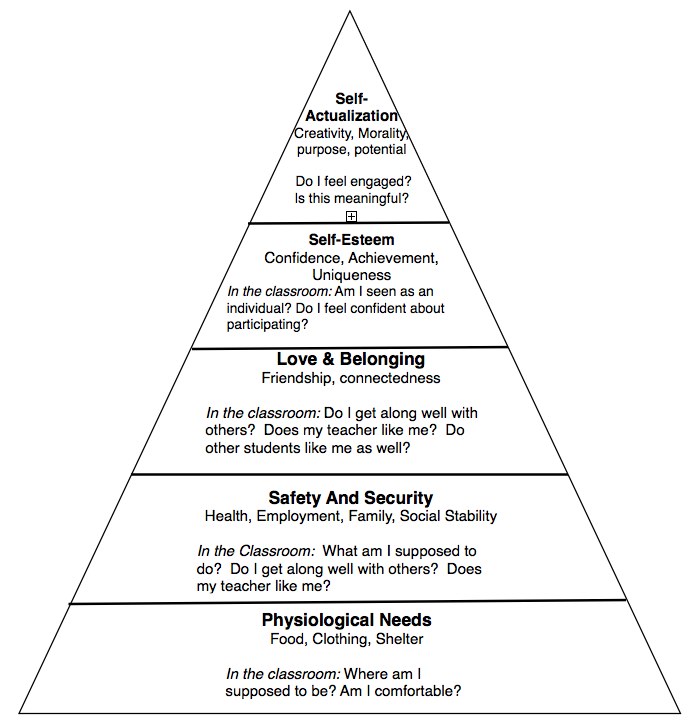

Homework shouldn’t be a punishment. If a teacher adds extra homework when the kids are bad, kids will naturally start to associate any form of homework as a form of punishment, not just “discipline”, which in its most authentic form means To Teach. Homework should be an opportunity to extend learning, to make connections with the outside world, and start to see how the classroom learning connects with their larger lives.

Now I know full well that some kids need more practice than others, or may memorize things faster than others. In which case, why do all kids need to do 35 math problems when some have mastered the concept in the first 5 or 6? The rest of those problems, for those students, is mere repetition and sheer tedium, teaching them nothing new. Teachers need to help figure out which students need more practice, or perhaps even a different kid of practice than blindly assuming repeating the same procedure over and over will make a kid smarter. In fact, it seems to me Einstein said the definition of insanity was doing the same task over and over again yet expecting different results. Maybe there’s room here to start thinking about homework, and what we want kids to get out of it.

Let’s not forget one of the options all teachers have is to ask their students not only how they feel about homework, but why. If they say it’s stupid and boring, then you need to ask the next question- Why? What about it is stupid and boring? How could we make it better? If you were in charge, how would you change the homework? Most teachers will be surprised that the majority of kids will give you thoughtful and insightful answers to these questions, and will take them seriously.

I think both teachers and students (not to mention parents) deserve to have more thought and purpose put into homework, and for homework to become a more collaborative process for everyone.

What do you think?

Could you differentiate the homework in your classroom? Why or Why Not?